THE DREAM CONSTITUTION

Learn about the history of the 72,000 letters sent by citizens to the Brazilian Constitutional Convention and how to consult them

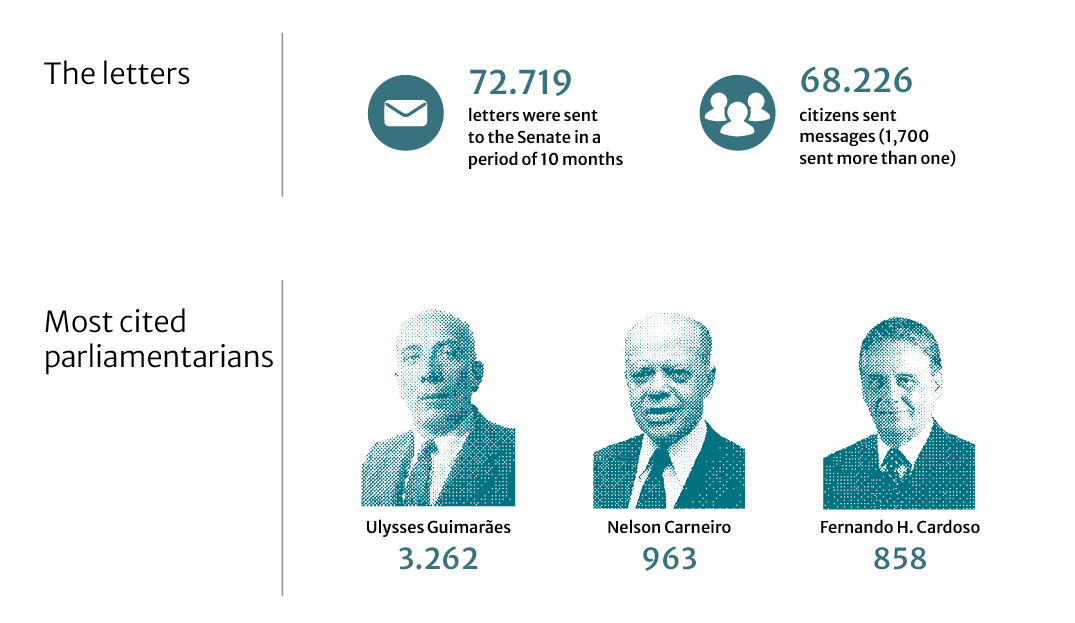

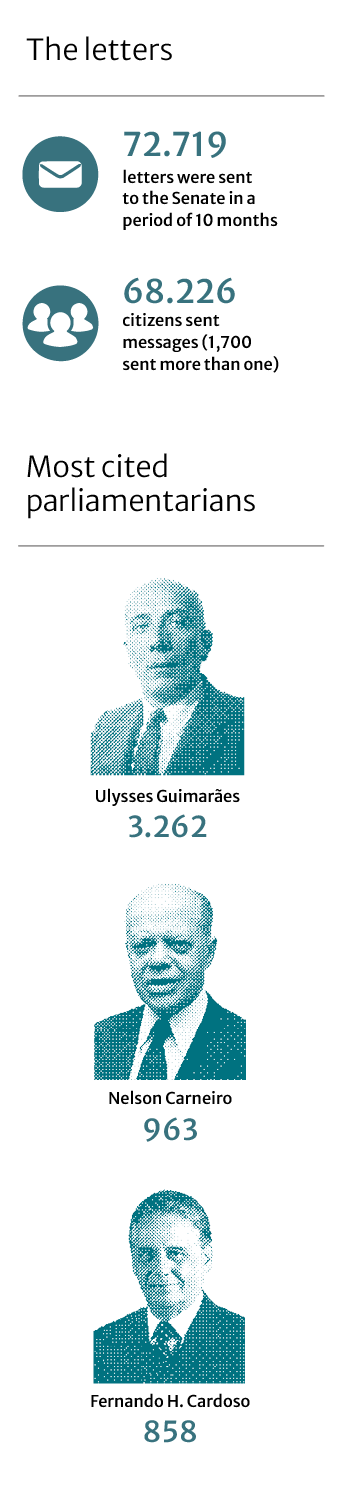

The passing of another anniversary of the 1988 Constitution on October 5th brings to mind one of the most important chapters in the 200th anniversary of the Senate: that of the popular mobilization for the construction of the country's highest law. One of the best examples of this history are the 72,719 letters sent by citizens to the constituents between 1986 and 1987. Until now, they were only accessible through a little-known database on the Senate portal. From now on, they can also be explored through a platform that makes it easier to search for themes, cities, and the names of the authors—a tool developed especially for this article (see below).

The initiative to invite people to contribute suggestions to the Constitution was part of the context of the country's re-democratization in the 1980s. After two decades of military dictatorship, society was signaling its desire for greater participation in political decisions. Between 1983 and 1984, the Diretas Já [Direct Elections Now] campaign brought millions of people to the streets of the main cities.

When, in 1985, the then President of Brazil, José Sarney, called for a Constitutional Convention, various sectors of civil society came together to take part in the process. The slogan "Constituinte sem povo não cria nada de novo” [Convention without the people brings no change] reflected the aspirations of the time.

This spirit was captured by the senators and deputies of the

Convention. They provided for participatory mechanisms in the

Assembly's house rules. More than a thousand people were heard

at public hearings. And 122 popular amendments organized by

associations received more than 12 million signatures and were

delivered to the parliamentarians. But that's another great

story of the Convention. The story of the letters to the

Constitution, told here, followed a different path.

This spirit was captured by the senators and deputies of the

Convention. They provided for participatory mechanisms in the

Assembly's house rules. More than a thousand people were heard

at public hearings. And 122 popular amendments organized by

associations received more than 12 million signatures and were

delivered to the parliamentarians. But that's another great

story of the Convention. The story of the letters to the

Constitution, told here, followed a different path.

Initially named Diga Gente [Say, People] and then Projeto Constituição [Constitution Project], the idea for the letters came from Senate civil servant William Dupin, who at the time headed the Special Projects Coordination Office at Prodasen—the body responsible for information technology in the House. The then chairman of the Constitution and Justice Committee (CCJ), Senator José Ignácio Ferreira, from Espírito Santo, supported the initiative.

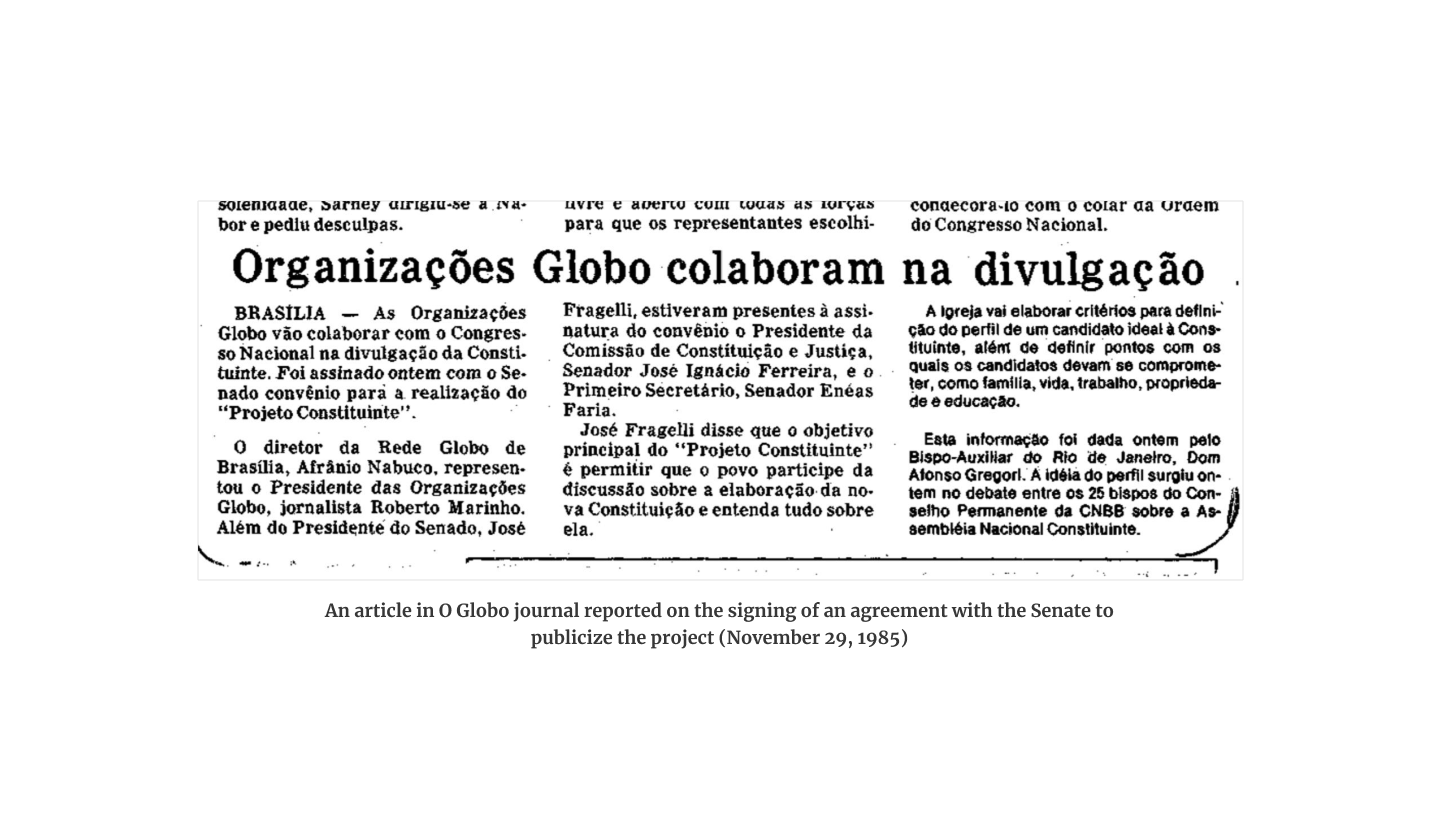

However, the high costs of the project led Dupin to seek support from the private sector. Mass media conglomerate Globo Organization financed part of the costs and ran advertisements promoting the campaign, in exchange for including the company's logo on the printed forms that would be distributed.

Although it ensured that the idea was viable, the solution was not without its critics. The pertinence of the partnership with a private company was seen as a risk to the impartiality that should characterize public administration. In any case, the project was launched in June 1986.

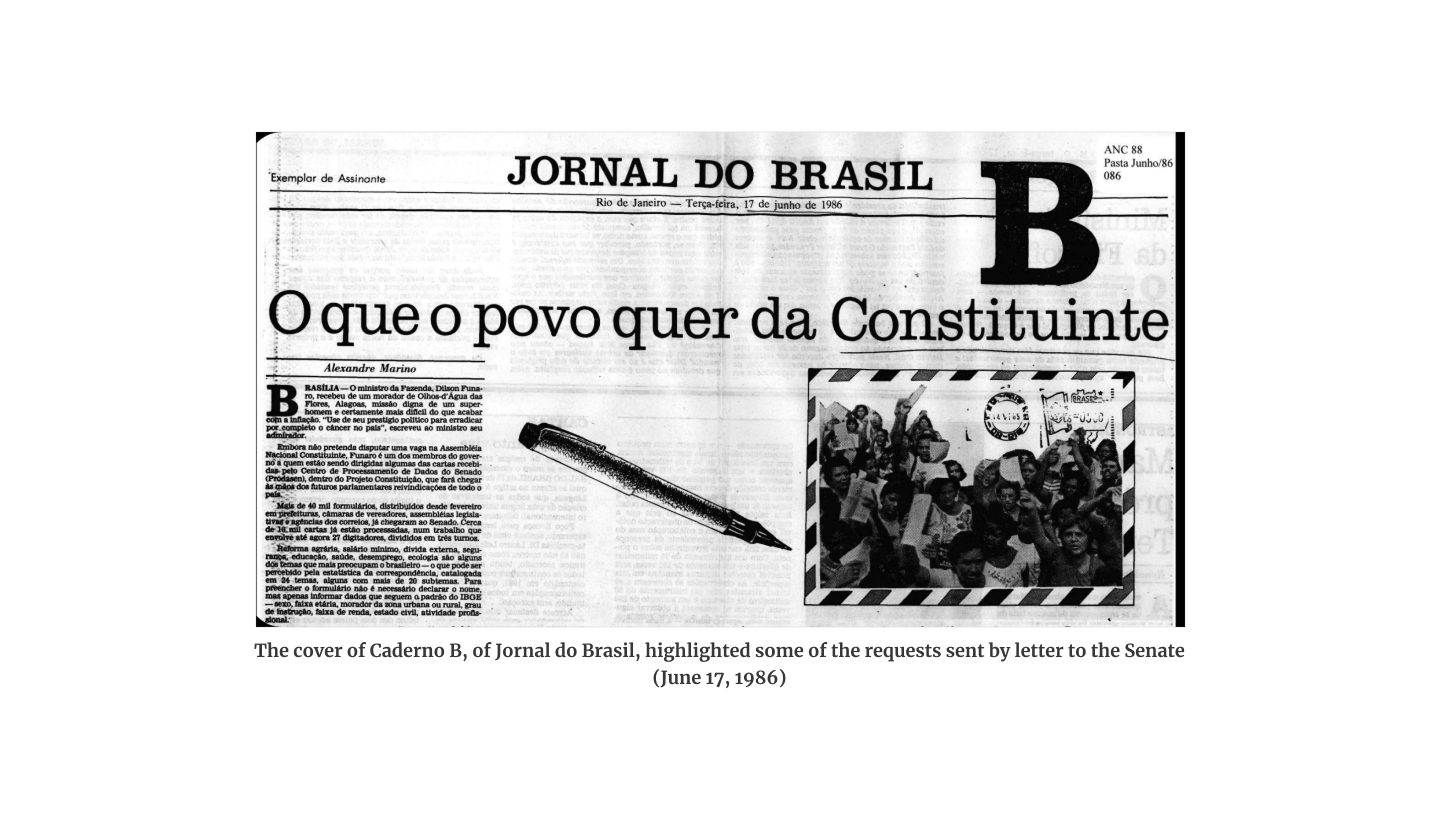

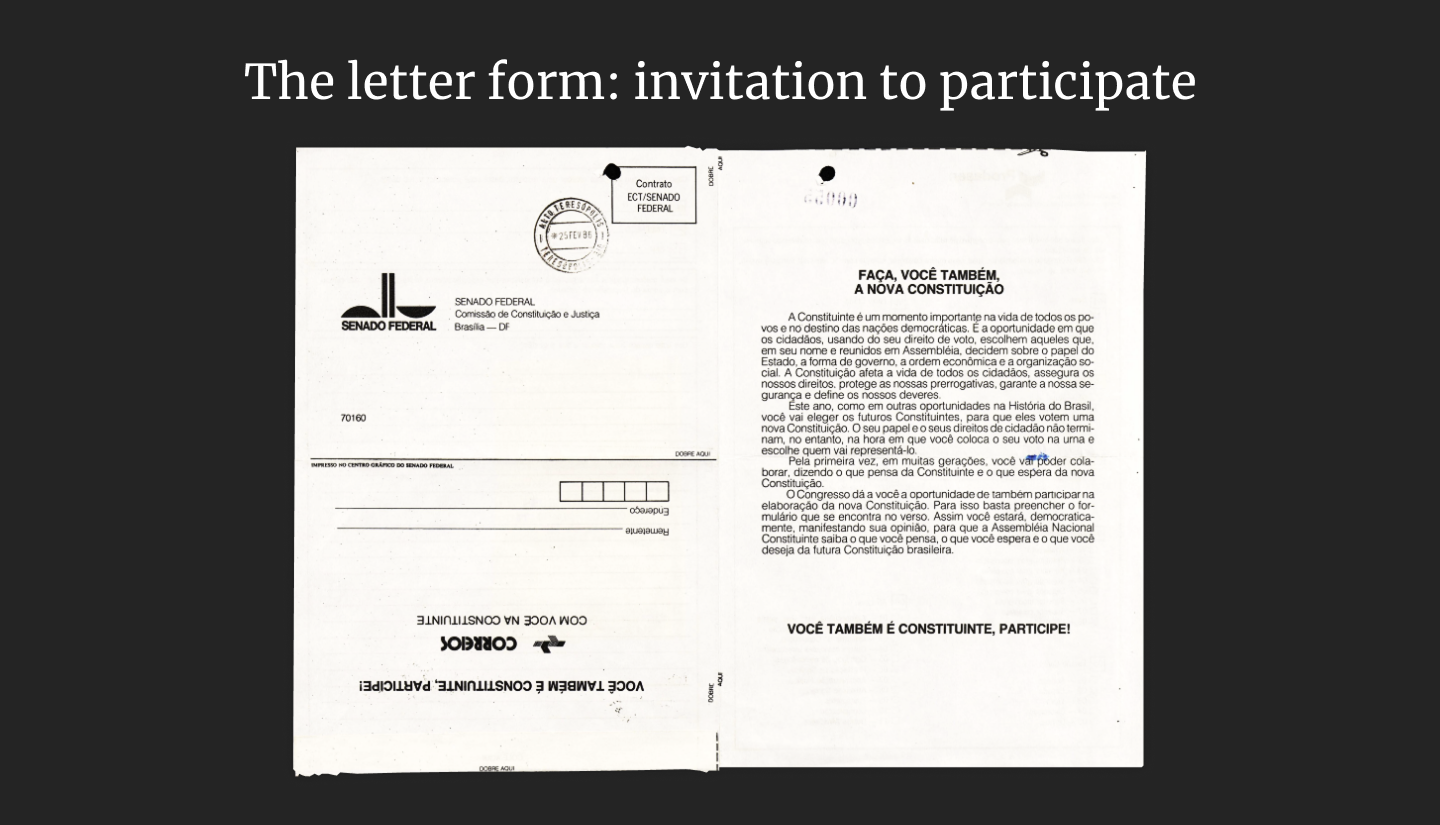

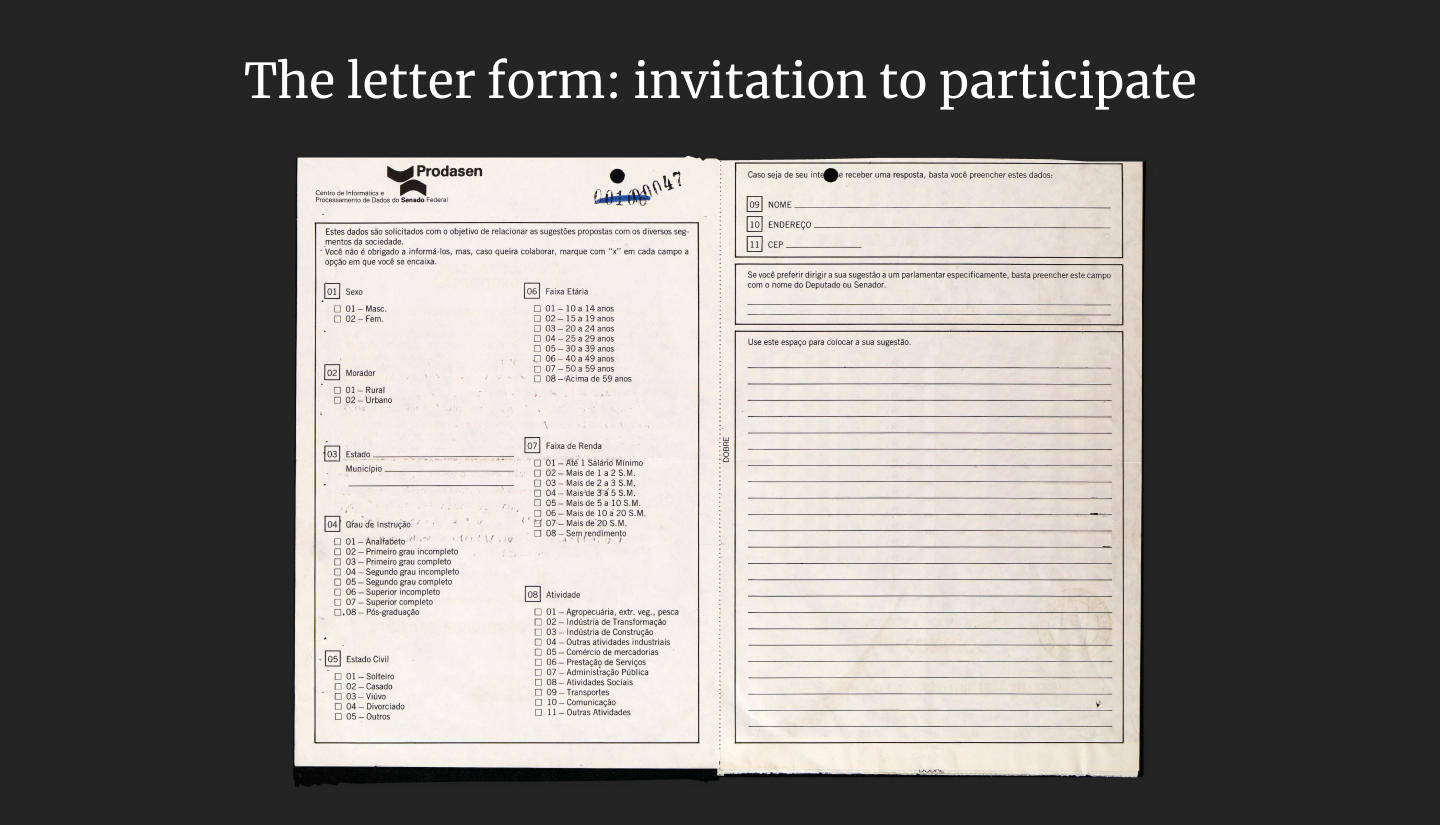

Five million forms were distributed to the municipalities in proportion to their population. The forms were available at post offices, but there were also collection points in town halls and legislative assemblies. In addition, political parties were able to deliver forms directly to their members.

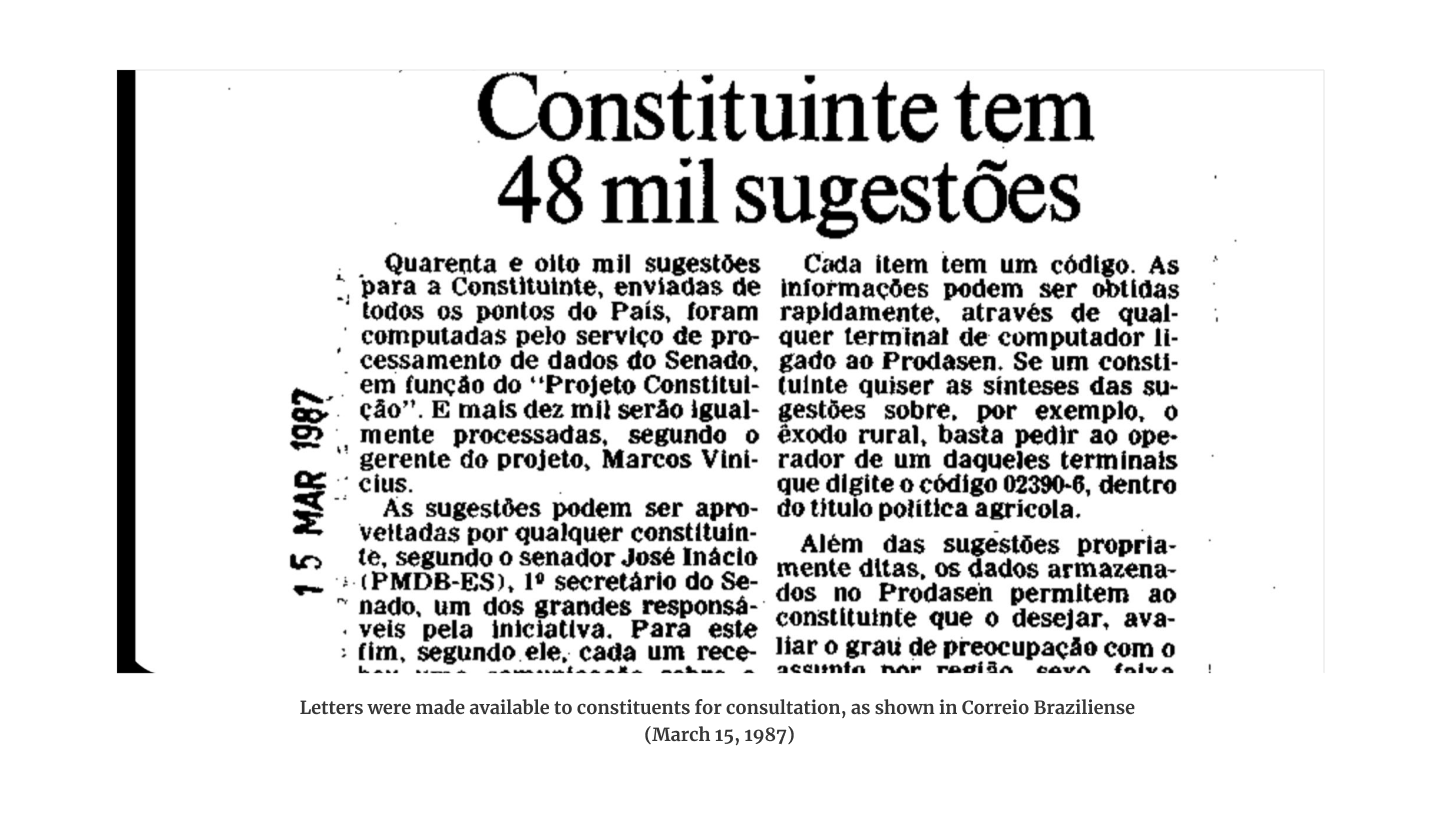

After almost a year, more than 72,000 completed forms arrived at the Senate. As they arrived, a group coordinated by Prodasen, including staff from the House and students from the University of Brasilia (UnB), sorted the messages into 24 thematic areas and typed them up so that they could be entered into a database in the newly created Sistema de Apoio Informático à Constituinte [Constitutional Convention Computer Support System] (Saic, in the original acronym).

Who were the authors?

In 1987, Francisco Alves Mendes Filho wrote one of the letters that reached Prodasen. In handwritten text, the message sent from the interior of Acre defended the preservation of the Amazon rainforest through the creation of extractive reserves.

The following year, just before Christmas, Francisco was shot dead on his doorstep at the age of 44. It was only then that the name Chico Mendes became known throughout the country as a rubber tapper leader and an inspiration for the environmental cause. The murder had repercussions around the world.

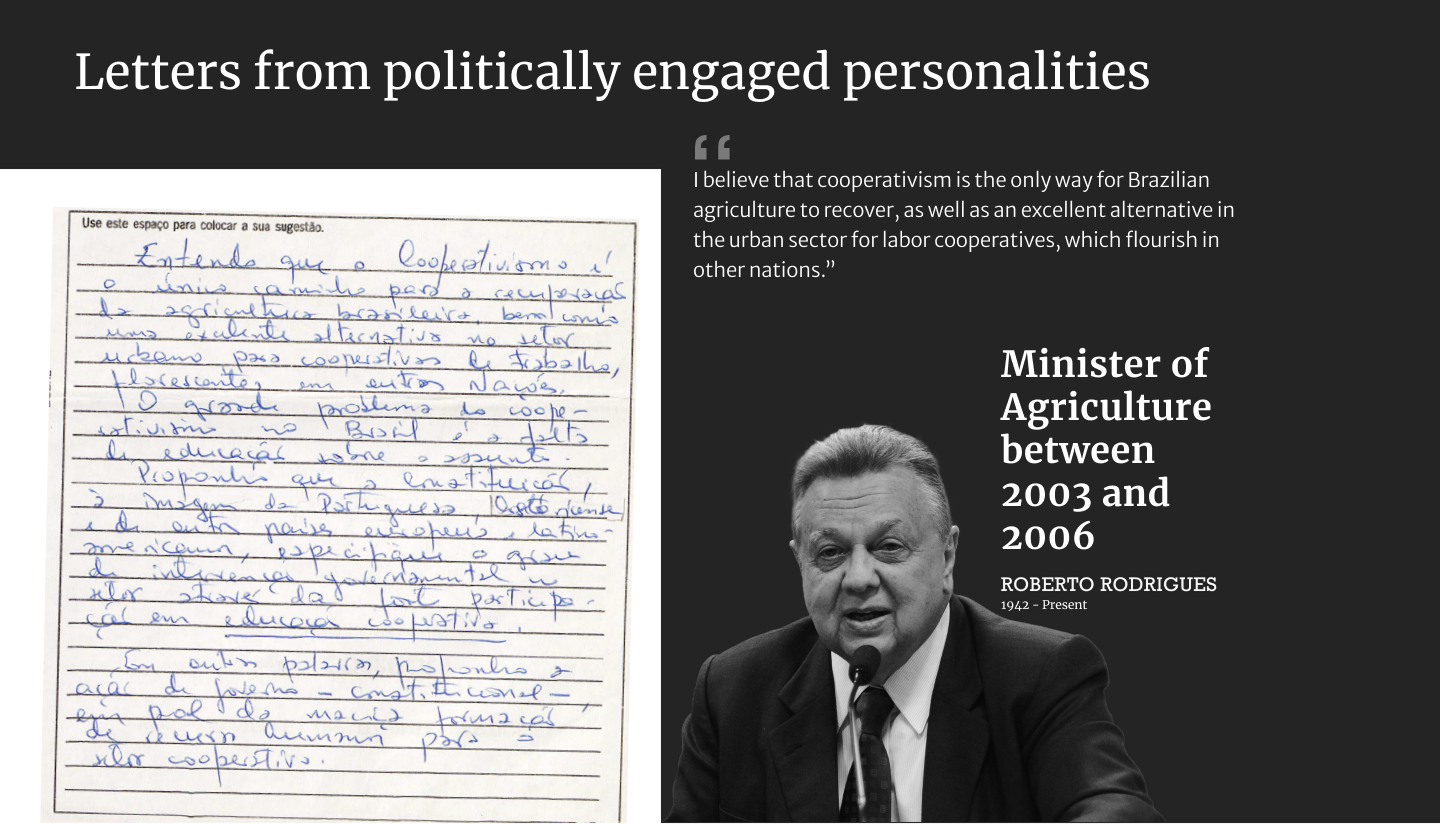

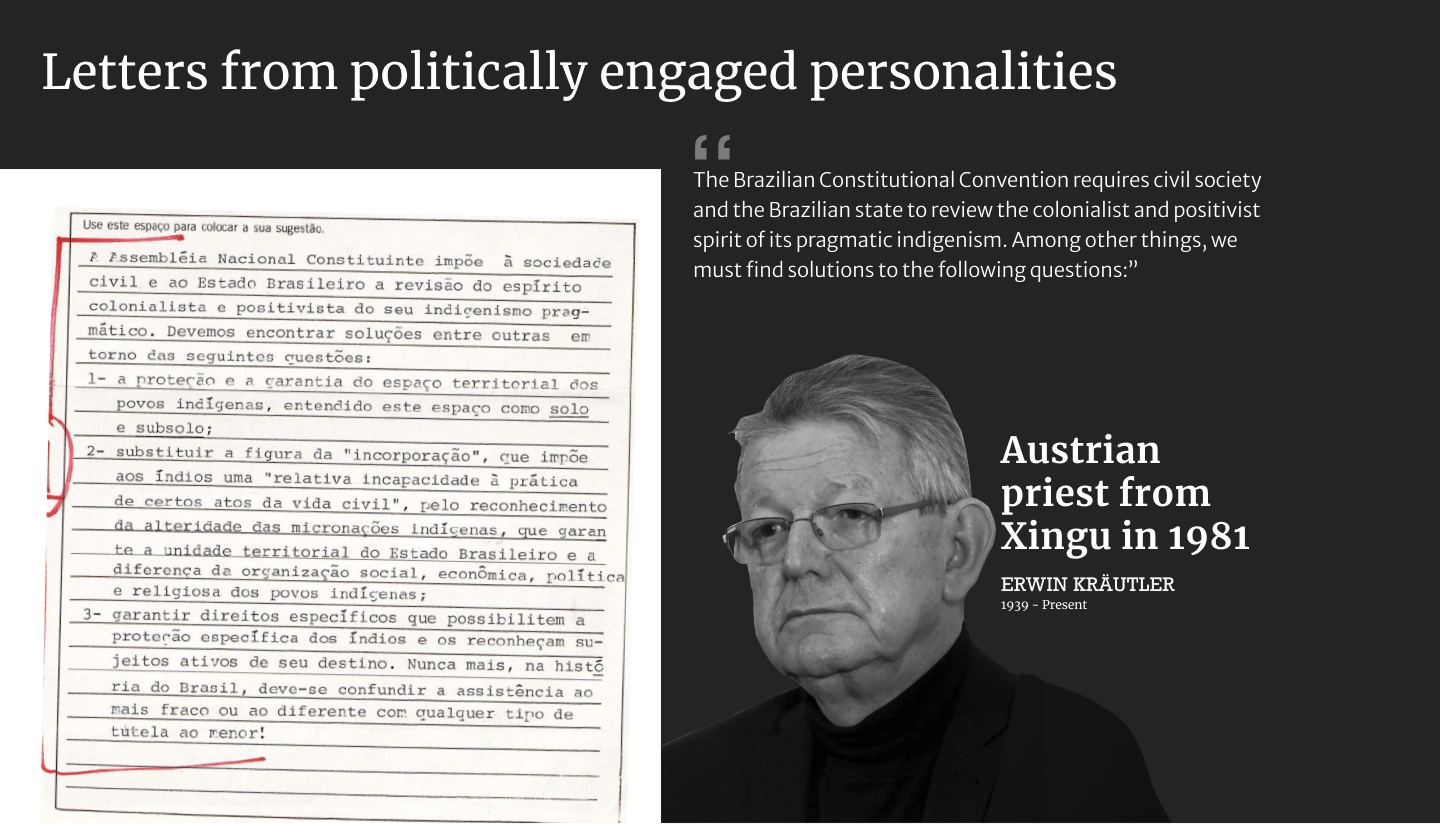

Although Chico Mendes' letter and those of other personalities draw attention because of the names of the senders, the collection stored at Saic reveals a country dreamt up by anonymous citizens.

—There is a population that is crying out for improvements in transportation, health, and education,—said French Brazilianist Stéphane Monclaire in an interview with Jornal do Senado in 2013.

Professor of political science at the Sorbonne University in Paris, Monclaire organized and co-authored the book A Constituição Desejada [The Desired Constitution, free translation], published by the Senate in 1991 with a sociological analysis of the suggestions sent to the constituents.

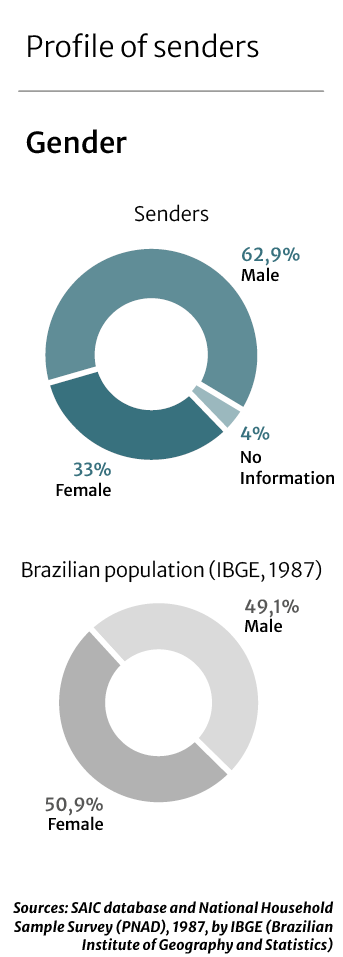

In the book, Professor Clóvis de Barros Filho, author of one of

the chapters and currently one of the country's most prominent

philosophers, states that the letters "are qualitatively more

important for science" than public opinion polls. Even

considering that the group of senders was not a representative

sample of the entire Brazilian population at the time.

In the book, Professor Clóvis de Barros Filho, author of one of

the chapters and currently one of the country's most prominent

philosophers, states that the letters "are qualitatively more

important for science" than public opinion polls. Even

considering that the group of senders was not a representative

sample of the entire Brazilian population at the time.

For him, by opening up a space for suggestions, without pre-formatted options, the Projeto Constituição's forms would provide more accurate analyses of citizens' political positions.

What were the messages asking for?

The more than 72,000 letters sent to the Senate generally contained informal appeals, without legal formatting.

—People are expressing their anguish about life's difficulties. And they expect everything from the Constitutional Convention. Everything, that is, a better life, —said Professor Stéphane Monclaire, in the same interview with Jornal do Senado (the professor died in Brazil in 2016 after almost 30 years dedicated to the study of Brazilian issues).

Monclaire saw in the letters to the Constitutional Convention a similarity to the cahiers de doléances [list of grievances] of the French Revolution of 1789, when the population had their complaints written down.

However, for him, the great innovation of the Brazilian project was the digitalization of the letters, which made it possible to consult them in different ways by cross-referencing the different profiles of the authors.

For this article, for example, the Saic database was subjected to an analysis using Artificial Intelligence (AI) with the aim of organizing the letters by the similarity of their content. In the study, natural language processing (NLP)—an area of computer science— techniques were applied to transform the texts into mathematical representations, allowing the AI to identify the themes.

The following image, called a "semantic map", graphically illustrates the results. The colors are thematic categories. The distance between them reflects the degree of similarity of the themes.

The largest volume, in red, brings together the letters that address several issues in a single message. The isolated poles show the articulation of interest groups, sometimes surprisingly. This is the case with the group of messages advocating the regulation of private detective work.

What has the Constitution incorporated?

Referendums are the most common way of consulting the population in the constitutional process. Between 1789 and 2016, 168 constitutions were submitted to referendums around the world, according to a thesis presented at the University of Texas by the American researcher Alexander Edward Hudson.

In this mechanism, the people approve or reject a ready-made text. In Brazil, the various participatory instruments used in the 1980s gave an innovative aspect to the country's constitutional process. It remains to be seen to what extent the people's suggestions influenced the final wording.

In his book A Constituição Desejada, professor Stepháne Monclaire says that "Saic has always been used below its potential" by delegates, academics, and the press. He says that some parliamentarians even complained about the then chairman of the Senate's CCJ, José Ignácio Ferreira, for supposedly having abused Prodasen's data "to appear as a delegate strongly committed to his work".

Responsible for constructing the semantic map that appears in this article, AI specialist and Prodasen employee João Lima says that although the degree of direct influence of the letters on the constitutional text is a subject of debate, it is possible to see reflections of the messages in the Constitution.

Lima, who heads the Senate's Legislative and Legal Information Solutions Service, highlights, for example, the letter sent in February 1986 by nurse Francisca Selene de Oliveira Claros, who lived in Manaus at the time.

"May it be approved by the Constitutional Convention: Health is a citizen's right and a duty of the State, and health care should be provided through a unified health system that serves everyone," wrote Francisca Selene, who was interviewed in 2007 by TV Senado for the documentary Cartas ao país dos sonhos [Letters to the dream country, free translation].

She also suggested that the private health sector should act as a complement to the public system and that the community should be involved in planning the healthcare system's goals and overseeing resources. It is not possible to know whether any delegate was inspired by these suggestions and presented them to the Constitutional Convention. The fact is that they all appear in the Constitution.

What is the letters’ legacy?

The letters to the Constitution represent the initial milestone of popular participation in the Constitutional Convention, says Fernando Trindade, a Senate's legislative consultant. He points out that the initiative was launched 11 months before the start of the Constitutional Convention's work, which was installed on February 1, 1987.

For the consultant, society's desire for greater participation in decisions about the country is reflected in various points of the Constitution. This is the case with Article 14, which for the first time in Brazil links the triad of popular sovereignty, universal suffrage, and direct and secret voting.

CEDI/Câmara dos Deputados

Trindade also highlights the constitutional provision for popular initiative bills. The Clean Record Act (Complementary Law 135 of 2010) is an example of this mechanism. In order to present a bill like this to the Congress, it is necessary to gather the signatures of at least 1% of Brazilian voters in at least five states.

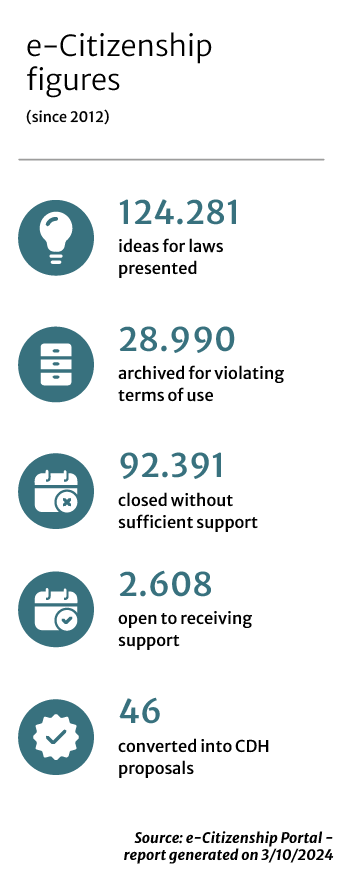

Another mechanism that preserves the spirit of popular participation present in the letters to the Constitutional Convention are the so-called legislative suggestions. They can be submitted to the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies. In the Senate, any citizen can individually submit their legislative idea via the internet, on the e-Citizenship Portal, linked to the Secretariat-General of the Board.

If, over the course of four months, the idea gathers the support of 20,000 people on the portal, it will go as a suggestion to the Committee on Human Rights and Participatory Legislation (CDH). If it receives a favorable opinion from the committee, it will become a bill.

—Representative democracy comes from the material impossibility of bringing the sovereign people together in a modern agora. But what was impossible has been made possible by information technology— Professor Stepháne Monclaire told Jornal do Senado.

The current director of Prodasen, Gleison Carneiro, agrees:

— Projeto Constituição consolidated Prodasen's role as an important pillar of the Senate, not only in terms of technical support, but also as a key institution for citizen participation and transparency in the legislative process.

Explore the Letters

This section allows you to search by names, states, cities, and letter themes. Search for family members and acquaintances. You can also try searching by keywords and suggested themes.

Use your browser's automatic translator to translate the content of the letters

Download the database in .CSV format with all the letters here

Data structured in a single spreadsheet.